Judith Westveer

Scientific Journalist

I am a creative academic who likes to tell stories about nature, and the Amazon rainforest is my biggest source of inspiration. After finishing a PhD in Conservation Ecology, during which I studied ways to protect and restore wetlands, I worked for several Peruvian environmental NGO's. Currently, I'm focused on creating awareness on the importance of nature.

Learn more about Judith Westveer

December 8, 2022

Roads, rice and ranches

The metal bridge in downtown Puerto Maldonado, above the mighty and murky Madre de Dios river, is not just any bridge. This 750-meter long suspension bridge, officially called the ‘Puente Guillermo Billinghurst’ after a Peruvian congressman, was finished in July 2011 and completed the 2600km-long Interoceanic Highway, which runs from the Atlantic Ocean through Brazil to several ports on the Pacific Coast in Peru.

The Interoceanic Highway was supposed to bring a boost in economy, creating a connection between the two oceans as well as between Peru and Brazil. Presidents from both countries promised the transport of goods to the Pacific coast and Atlantic coast, opening up to Asian, US, European, Peruvian and Brazilian markets.

In 2017, it was found that the highway was practically not being used for trade. The average circulation was only seven commercial vehicles per hour, an extremely low average. According to the Peruvian authorities, there were basically no Brazilian products on the way to the ports in Peru.

Since the completion of the Interoceanic Highway and the easy connection between Brazil and Peru, an increase in drug trafficking, illegal gold mining and a surge in agricultural expansion has been witnessed in Madre de Dios.

The bridge, allegedly the symbol of economic prosperity, is now only heavily trafficked by fast motorbikes, colorful tricycles, worn minivans and the odd truck. It did bring change into the region however. Since the completion of the Interoceanic Highway and the easy connection between Brazil and Peru, an increase in drug trafficking, illegal gold mining and a surge in agricultural expansion has been witnessed in Madre de Dios.

I’m partially impressed by human ingenuity and partially very worried and wonder, who are the people that travel across the Interoceanic Highway to create a new life for themselves as farmers? And can these new farmers find easy and cheap ways to sustainably run their farm in the middle of the rainforest?

Crops and cattle in the rainforest

Creating a good road through forested areas leads to the creation of smaller side roads that lead to crappy off-shoot roads that lead to tiny trails. A new network is created that from the sky resembles a branched tree, but they are roads that lead to deforested plots of land.

Already 3% of Peru’s rainforest has been lost to deforestation since 2002, with one of its leading causes being agricultural expansion. Almost half of all of Peru’s agricultural area is located in the Amazon basin, since the high altitudinal Andes and arid Pacific coast won’t allow each desired crop to grow. With the agriculture sector representing 7.5% of the country’s GDP and the economy continuing to grow, agricultural products are likely to remain important sources of government revenue and economic development.

We have all seen images of the massive soy and palm oil plantations in the Brazilian Amazon, with a stunning 11 thousand square kilometers deforested in 2020 alone. However, Peruvian palm oil makes up only 3.7 percent of Latin American production and Peru does not grow soybeans in commercially significant quantities, nor does it currently produce soybean meal used for livestock feed. A 20-year survey of land-use change, showed that post completion of the highway in 2011, Madre de Dios switched from mainly forest-based extractive industries, such as harvesting Brazil nuts and aguaje palm fruit, to small-scale agriculture and cattle ranching. Luckily, the massive soy and palm oil monocultures are not yet present in Madre de Dios.

A solid spatial analysis of forest loss in Madre de Dios showed that the main drivers of deforestation in this region are gold mining, agriculture and pasture fields. While an analysis by the Climate Advisors states that small-scale coffee and cacao cultivation cause the majority of agriculture-driven deforestation in the tropical areas of Peru, this does not correspond exactly with the lowland regions of southeastern Peru. This doesn’t mean people are not having their hot coffee and eating delicious chocolates, it just means that other crops are more suitable or popular in this region.

The dominant agricultural ‘crop’ in 2020 however was grass (Brachiaria brizantha). This type of grass is used to feed cattle and therefore directly represents the surface of pasture in the area.

Thanks to a recent and very detailed National Agricultural Area Map, we can see that the nutrient-poor soils of Madre de Dios are mostly used for rice, corn, banana, cassava, beans, citrus, cacao and to a lesser extent vegetables and soybeans. Papaya has been a very popular crop in the region, experiencing a production boom shortly after the Interoceanic Highway was finished and still presenting 18% of the national produce, though production numbers are declining every year. The dominant agricultural ‘crop’ in 2020 however was…drum roll…grass (Brachiaria brizantha). This type of grass is used to feed cattle and therefore directly represents the surface of pasture in the area. In 2020, pasture land represented 34.4 percent of the agricultural sector, almost 8% percent higher than the previous year.

What are the main techniques being used in tropical farming?

Agricultural production in Madre de Dios is mainly based on ‘slash-and-burn’ or ‘migratory-agriculture’ techniques and are often small-scale, meaning that the products end up at the family dinner table or local markets, generally without any major international export revenues. This practice is carried out by Puerto Maldonado inhabitants (the largest city in Madre de Dios), as well as temporary Andean, Bolivian or Brazilian immigrants who easily learn this technique.

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a method in which all trees and shrubs in a specific plot are cut and burned, and the nutrients in the ashes act as fertilizer. The plot is used for a production cycle and then left to rest. This is an often used technique in regions with nutrient-poor soils to mine the energetic and nutrient capital of the natural forest soil/vegetation complex, which often provides the only source of nutrients for cultivation.

However, there are some serious disadvantages to this agricultural method:

- First of all, the plot has to rest, or ‘lay fallow’ for enough time to replenish its nutrient levels. This could take several years, and each time the plot goes through a cycle of production, it needs to rest longer before the soil nutrients can support another crop cycle. Not many farmers have enough land to let the plot lay fallow for enough time and start a new cycle early, eventually depleting the soil beyond repair.

- Secondly, the ashes from vegetation burn increase pH values and carbon values only in the first months, but the practice of slash-and-burn after 12 months results in lower values of pH and nutrients indicating this practice eventually contributes to the reduction of soil fertility.

- Third, if the burn is performed right before major rainfall, the nutrients run off the land instead of getting absorbed into the soil, completely counteracting the purpose. And last but not least, as the land burns, the fire can get out of hand and larger plots are burned than initially intended. Especially with a drier forest in recent years due to climate change. All and all, tricky business.

One brave woman who recently took on a 7-hectare farm close to the Interoceanic Highway is called Carmen Pilares Alvarez. She is a Puerto Maldonado native, and has a plot of corn, banana and a couple cacao trees about 34 kilometers from the city.

I speak to her about her agricultural techniques, with which she is still experimenting. She does not use pesticides, herbicides or fire, and takes on farming with a pretty relaxed trial & error approach: ‘We used a specific machine to plant the corn last year, but perhaps it was the wrong piece of equipment since nothing really came up, but we will try again this year’.

Her neighbors do use pesticides and fire to control weeds, which are the most common methods in the region. But Señora Alvarez now has adapted a method in which she puts cardboard on the soil to prevent any weeds. Her ecological efforts are rewarded by seeing wild animals, such as tapirs and peccaries, crossing her land, which she doesn’t mind at all.

It’s a completely new experience for her. ‘I usually work as a teacher at the local school in Puerto Maldonado, but this opportunity arose and I love to be outside and work in the fresh air and sunshine.’ She has a bunch of chickens and dogs running around at the farm, and goes there as often as possible. She then touches upon a sensitive topic: ‘We have to make sure the farm looks well-tended and occupied, because otherwise people will come and take the land from us. The only way to prevent this is to demonstrate our presence and always have our property documents ready to show to any stranger who inquires.’

Illicit activities around the interoceanic highway pose a tremendous challenge to farmers ánd policymakers in Peru. Since the region is so vast and now easily accessible, a chain of illegal activity has led to increasing deforestation as mafia-like actors invade land, claim property or pay owners to abandon their plots, and subsequently mine the land for gold.

Is there a sustainable way of agriculture and cattle farming?

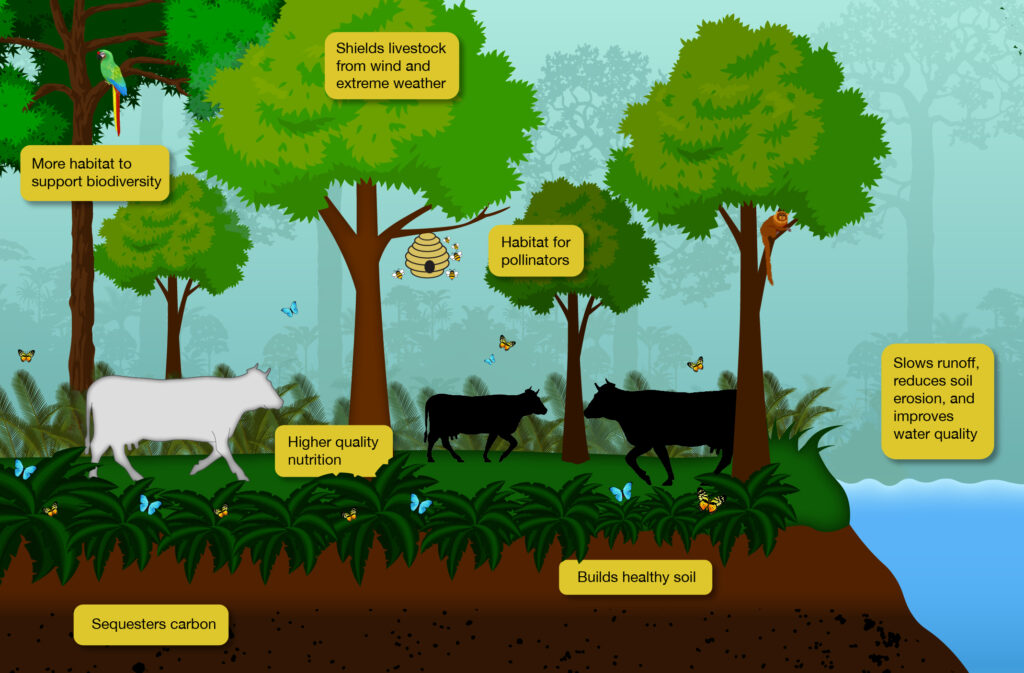

Imagine fields with trees, not quite as densely packed to call it a real forest, but open enough for large domestic livestock to roam, while they blissfully munch on some leaves. The trees can have fruits and other usable crops, while monkeys jump from tree to tree, insects pollinate as they are supposed to, the soil is moist and it’s nice and shaded. This is not a fairytale, this is called a silvopastoral system and is being trialed in different regions with different tree compositions.

The benefits of trees in cattle pastures include:

- enhanced soil nutrient cycling and soil formation,

- an increased rate of recovery of compacted soils,

- reduction in water and nutrient runoff and soil erosion,

- while providing additional habitat to support biodiversity,

- mitigation of climate change via carbon sequestration,

- increased ecological connectivity,

- and cows get higher quality nutrition

Dr. Lucy Dablin, lecturer in Environment and Sustainability at the Open University in the UK, has spent many years in Madre de Dios and agrees with Señora Alvarez’s story on land grabbing: ‘Cattle ranching in Puerto Maldonado is often not focused on producing beef. A share of landowners use cattle farming as a cheap way to maintain a presence on their land, which is necessary due to the common practice of land invasions. Local criminal gangs know that many rural people don’t exactly understand the land rules and can easily take advantage of that. With not enough income to effectively protect forested land, which makes land grabbing easy, people resort to felling trees and start a poorly-managed cattle ranch.’

Cattle ranching in Puerto Maldonado is often not focused on producing beef. A share of landowners use cattle farming as a cheap way to maintain a presence on their land, which is necessary due to the common practice of land invasions.

Dr. Lucy Dablin

Lucy had an agricultural ‘eureka-moment’ during her PhD research in the rainforest region of Northern Bolivia, where she was developing agroforestry systems with migrant communities to improve the sustainability of farming practices. One day, some cows broke into one of the experimental plots and started munching on the planted trees – a big part of their two-year work ended up in the cows’ stomachs. But for Lucy, this was the start of her silvopastoral research: ‘I thought, hey, why are we feeding cattle in the Amazon African grasses when they can eat native trees? Why are we taking an area of the highest terrestrial productivity and turning it into one of the least productive systems?’.

Subsequently, she set up her own research farm in Puerto Maldonado, Centro ReVerde, where she manages experimental silvopasture systems using native tree species. Her first visit to the region was in 2008 and many more since then, has led her to witness first-hand the expansion of cattle farming and agriculture in Madre de Dios. With the attitude ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’, she started experimenting with cattle ranching in order to improve the practice.

As a previous resident of Madre de Dios, she wanted to implement her findings from Bolivia in Peru, ‘I wanted to see how a silvopastoral system could work in this region, so I started by surveying which tree species cattle were browsing. I interviewed cattle farmers to identify potential tree species, did a literature study and eventually ended up with a list of trees that were edible to cattle, that grew fast, withstood sunlight, could grow in the competitive african grass pastures, and produced a high proportion of leaf biomass. We planted an experimental silvopasture system on 4 hectares that contained 4,500 saplings of five tree species and after 24 months we allowed cattle to browse the trees. The results demonstrated, for the first time in the Amazon, that silvopasture could produce more nutrients for cattle than the traditional, grass-only monoculture widely used by farmers. It was a huge experiment, and was made possible by the help of 200 volunteers.’

Sustainable cattle farming means maintaining the fertility of the pasture without decreasing cattle production. Silvopasture can offer shade and shelter to animals, reducing their stress, trees can bring nutrients up from lower soil horizons and a more diverse ecosystem can control some common pasture pests and parasites reducing the need to burn the pastures.

Sustainable cattle farming means maintaining the fertility of the pasture without decreasing cattle production and that is why Lucy focused on the nutritional contribution of tree foraging to animal health. Pastures will typically decline after 15 years as the grass gets burned and soil nutrients get unevenly distributed. Silvopasture can offer shade and shelter to animals, reducing their stress, trees can bring nutrients up from lower soil horizons and a more diverse ecosystem can control some common pasture pests and parasites, such as ticks and worms, reducing the need to burn the pastures.

Her main purpose was to proof that trees in a pasture can actually increase cattle health and production, and she soon started to see the accompanying side effects of restoration, as night monkeys (Aotus miconax), jaguarundis (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), birds, rodents and other mammals returned to the forest farm.

The future of sustainable cattle farming holds many options, according to Lucy. ‘There are novel silvopastoral methods for animal health, for example with a tree-species (Inga sp.) that attracts a parasitoid wasp that predates on ticks. But also by increasing technical assistance to farmers, to adopt silvopastoral systems and rotational grazing. ‘If we don’t help these farmers they are going to be trapped in poverty, owning a piece of desertified land. We need to intervene now, while the land is still relatively healthy. Bringing it back from the brink of ecological destruction will be a lot more expensive.’

How can farmers find these sustainable methods?

With so many new farmers, new organizations are also arising to educate people on best practices. One of those is AGRAP (Alliance for Regenerative Ranching in the Peruvian Amazon), which has been demonstrating the value of silvopastures as an alternative way of farming. While each silvopastoral system has mutually beneficial elements for soil, cattle and farmers, the specific aim of AGRAP is to include timber as a cash crop on the cattle pastures in order to benefit the farmers’ profits and reverse deforestation.

The AGRAP project was created in order to get knowledge on silvopastures, also called ‘regenerative ranching’, implemented in the field. They are funded by UK PACT, and delivered in partnership with WWF (World Wide Fund for Wildlife), the Climate Group, and the Tropical Forest Alliance.

Nelson Gutierrez, Forest Carbon Specialist with the WWF-Peru team tells me more about the successes of this project: ‘We started the project in 2018, as part of a global initiative called GFC Task Force, to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Our main objective is to promote regenerative ranching techniques. Besides hosting workshops and courses on these techniques, we actually started 10 new field schools in rural areas that are used as knowledge centers for experimenting and learning.’

Señor Gutierrez is not only extremely excited about the environmental gains, but also about the social aspect of the project: ‘About 40% of the farmers close to the Interoceanic Highway have not farmed before, and many of them have little knowledge on organic yet profitable ways of farming. Since we started this project, we see how fast the mindset of people can change. The wives of farmers and sons and daughters are also keen to participate, and we appointed specific farmers as local project leaders in order to have a more effective outreach. Entire communities were suddenly engaged in a more sustainable and healthy way of cattle farming.’

The project turned out to be a big success with now almost 300 cattle farmers in the region, all along the Interoceanic Highway, adapting to a silvopastoral system.

The project turned out to be a big success with now almost 300 cattle farmers in the region, all along the Interoceanic Highway, adapting to a silvopastoral system. So far, the project has created a mosaic of cattle farms with wooded areas. In this silvopasture technique, the wooded areas help to protect local biodiversity as well as provide farmers with extra, diversified income from forest products such as timber.

I ask señor Gutierrez what the main barriers are for cattle farmers to adopt this sustainable technique. ‘It’s mainly a lack of knowledge and communication. They think it’s more expensive to work sustainably. Also, the farmers in Peru do not work in massive monocultures but their farms are often a mix of crops and livestock. This demands them to be a jack-of-all-traits, but results in being a master of none of the farming techniques. Besides that, new farmers often don’t understand how fragile and nutrient-poor the soils are in a tropical rainforest ecosystem, since they are not from here and don’t know how to work with this.’

AGRAP will continue its efforts, find funds for future workshops and work directly with the farmers. Their latest plan is to build a monitoring system to see how the sustainable farmers are doing, so it’s not just an instruction without a follow-up. Similarly, for crop farmers there are ways to transition into agroforestry. Several global organizations sponsor agroforestry solutions for landowners in Peru.

Keeping the forest standing by growing a mix of trees and shrubs alongside crops, doesn’t only help to keep soil nutrient and moisture levels retained, but also helps with crop pollination and organic pest control.

From small-scale farm to environmental tipping point?

Governmental stimulation of agricultural expansion started a long time ago. Between 1993 and 2011, the government of previous presidents Alejandro Toledo and Alan Garcia launched several rural credit programs that fostered immigration from the Andes, resulting in a progressive increase in regional crops such as rice and corn, the expansion of cattle ranching, and urban growth of Puerto Maldonado and other smaller towns in the north of Madre de Dios.

These agricultural credits for everyone and anyone, with a relatively low interest rate, still exist. In 2021, The Regional Government of Madre de Dios, successfully got Peruvian bank AGROBANCO to open 67 million soles (19 million dollars) in agricultural credits, allowing agricultural producers in Madre de Dios without a credit history to qualify for the granting of these resources.

So, agricultural expansion and cattle ranching will continue, and with that deforestation and habitat fragmentation. What about some short-term solutions and long-term effects?

Besides a quick and large-scale transition to agroforestry and silvopastoral systems (hopefully fully sponsored by the government one day), it would be useful to install large and solid conservation corridors. Developing habitat corridors is considered one of the few effective methods for responding to the risk of large-scale land conversion. In a shared effort, the Amazon Conservation Association, designed 3 corridors in southeastern Peru based on a land-use mosaic, which includes an array of rights-holders and land tenures in addition to conservation areas. Supported by both science and community engagement, each corridor design considers social and political dynamics as well as ecosystem processes. Anchored by large protected areas, these conservation corridors consist of a patchwork of land uses, which permit economic development while allowing for gene flow and species migration.

The rainforest generates approximately half of its own rainfall by recycling moisture as air masses move from the Atlantic across the basin to the west. At some point, deforestation will likely reduce this moisture cycle to a point where it will no longer support rainforest ecosystems.

The worrying part is that we seem to be running out of time. Many articles by the late Tom Lovejoy and a 2019 report called ‘Nearing the Tipping Point’ describes how 20-25% forest loss leads to increasingly drier conditions that could result in forest fires on a massive scale, which ultimately lead the Amazon to approach a ‘tipping point’. The rainforest generates approximately half of its own rainfall by recycling moisture as air masses move from the Atlantic across the basin to the west. At some point, deforestation will likely reduce this moisture cycle to a point where it will no longer support rainforest ecosystems. Prospects are that we would reach that tipping point in 15 years, if deforestation rates continue as they currently are.

The ‘Nearing the Tipping Point’-report recommends promoting sustainable agriculture and infrastructure programs, increasing forest protection monitoring and enforcement, expanding protected areas, and strengthening reforestation efforts as means of curbing the rising deforestation rates in the Amazon.

This advice is in line with an ambitious statement from the former Peruvian Minister of Environment Antonio Brack Egg in 2008, saying that 80% of Peru’s primary forest can be saved or protected if major investments came through for, amongst others, sustainable forestry development. Using already disturbed plots of land for agroforestry instead of clearing pristine rainforest, could be enough to provide for all of Peru’s land use needs. Unfortunately, Minister Brack’s plans never truly came to fruition.

For now, the Interoceanic Highway is not going anywhere and new off-shoot roads are going to emerge, leading to new plots of deforested land. But instead of seeing the large bridge in Puerto Maldonado as a symbol of economic prosperity, let’s see it as an entry gate to a region with sustainable agricultural practices. People that traverse the bridge and drive on the Interoceanic highway can be people who want to create a better future for themselves and the planet.