Judith Westveer

Scientific Journalist

I am a creative academic who likes to tell stories about nature, and the Amazon rainforest is my biggest source of inspiration. After finishing a PhD in Conservation Ecology, during which I studied ways to protect and restore wetlands, I worked for several Peruvian environmental NGO's. Currently, I'm focused on creating awareness on the importance of nature.

Learn more about Judith Westveer

March 22, 2022

On a quest for gold

The first time I visited Madre de Dios, Peru, was in 2010. I took a boat up the Tambopata River, and saw that the water was laced with golden glitter dust. It felt like I was dreaming, being surrounded by a lush green jungle, blue skies, while floating on a river of gold. I fell in love with the place. Last year, I returned to the region. I traveled up the Madre de Dios river and got out of the boat utterly heartbroken.

I see a foreign landscape, where large piles of gray pebbles and brown sand rise up next to muddy ponds, which are topped with a frothy residue of an unfamiliar substance. Hills and potholes alternate in a surface that looks like a massive scar from a bad case of the chickenpox. The dominant colors are monotonous gray and muddy brown. The smells are industrial; odors of petrol and oil predominate. The sounds are mechanical, a continuous booming and bustling generator, tok-tok-tok-tok-tok, that never stops, not even at night. The sounds of the gold mine echo deep into the forest, and even after my ears get used to the sound, my body feels the bass incessantly.

The endless landscape of sand and stone is nothing like the rainforest that originally stood here. It’s the opposite world, and it’s clear that the ecosystem has literally been turned upside down. A tropical rainforest is normally a source of life, with unequaled biodiversity of plants and animals. Huge trees, with a different microhabitat on every square meter. A home for large predators like jaguars and pumas. A breeding ground for birds, high in the branches, and for fish, deep down in the wetlands. This wealth is now nowhere to be seen.

I keep wondering what happened. Why here? Why to this extent? Where are these illegal miners coming from, and what can be done to stop this? I decide to go on a personal quest for gold, but I want answers instead of jewelry.

Why is there gold mining in a rainforest?

Let’s talk about geology before diving into ecology, history and economics. The reason why people excavate the soil to look for gold, specifically in Madre de Dios, is a result of geological processes. When the mighty Andes were formed, they pushed up heavy metals that had sunk deep into the Earth’s core when our planet was formed1. In the long process of continental and mountain range formation, gold moved closer to the Earth’s crust and became accessible. The geographical position of the rainforest of Peru, lying right next to the Andes, created a unique situation where gold is embedded in the sediment underneath a massive forest. Yet another geological effect makes the Madre de Dios a real hotspot for gold. The tropical rainforest, lying in the foothills of the Andes, is jam-packed with rivers and streams, receiving all the runoff from the mountains. The water carries gold that slowly erodes from Andean rocks. It has been found that at places where glacial environments turn into melt-water environments are characterized by an increase in gold content2.

However, gold cannot be found in nuggets here, as in the north of Peru, but only in tiny fragments. Those ancient glaciers that slowly eroded the sediment layers affected the size of the gold fragments, leaving only golden dust to be found in river and stream beds. These ‘gold placers’ in mining jargon are hard to mine, and require very invasive and inefficient techniques to collect the precious element3. The only way to mine this alluvial gold (alluvial meaning sedimentary) is to excavate the soil of streams and river beds entirely and run the sediment through a number of machines and processes after which the little specks of gold remain.

Peru has several regions with gold deposits that are mined; the largest in surface area is Yanacocha. The Yanacocha Mine is an open pit mine located in Cajamarca and produced an estimated 340,000 ounces of gold in 2020 . Besides open pit mines, there are underground mines, such as the Marsa Mine in the region La Libertad, which produced an estimated 165,000 ounces of gold in 2020. This Peruvian region has the largest share of gold production, amounting to more than 29 percent of the total output in the country. To put these numbers in perspective, Peru extracted 120 tons in 2020, making Peru the eighth largest gold producer worldwide in that year . The gold production figures for 2021 still vary between sources, but some platforms say that the gold extraction dropped to 97 tons, making Peru the twelfth largest gold producer last year .

Besides negative social effects, including health issues from mercury exposure like high incidence of anemia and neurotoxicity among exposed children, increased prevalence of tropical diseases such as malaria, and a lack of access to health, education, and sanitation services in mining camps, this kind of illegal mining is also associated with organized crime, drug trafficking, human trafficking and sexual exploitation, all of which are prevalent at illegal mining sites.

The surface mines and the underground mines both have a strictly controlled excavation process. In comparison, alluvial gold mining is much worse for the forests and climate, releasing carbon from both aboveground forest and underground deposits.

The invasiveness of the alluvial mining process is easy to see in the most infamous mining area in Madre de Dios, called La Pampa. This area, translated ‘The Plains’, is the largest illegal alluvial gold mine of Peru, and the destructiveness of the mine can be seen on many levels . Besides negative social effects, including health issues from mercury exposure like high incidence of anemia and neurotoxicity among exposed children, increased prevalence of tropical diseases such as malaria, and a lack of access to health, education, and sanitation services in mining camps, this kind of illegal mining is also associated with organized crime, drug trafficking, human trafficking and sexual exploitation, all of which are prevalent at illegal mining sites . While these negative social issues are not directly obvious, the environmental destruction of the industry is – and I’m about to get up close and personal with this ugly process.

Why is this form of mining so destructive?

I met Katy in a shared taxi from the tiny town of Laberinto to Puerto Maldonado, the largest city in the region. She looks tired and asks if I have children – I say no. She does have children, four to be exact, a husband, and a couple of gold mines. With a bottle of rum, I show up at her house the next month, asking if I can visit the mine. She says yes and takes me to one of the mines. She says we have to be careful because the military is bombing the other one. We take a tricycle to a place outside of Laberinto where, yet again, it’s the classic picture of gold mining: high heaps of pebbles with deep pits of murky water. I see old rusty dredges and generators laying around, a load of plastic waste, and pieces of tarp that are bound to end up in the river next time the water rises. She tells me how the process works as we walk around the mine.

The procedure of alluvial gold mining isn’t exactly rocket science:

- An area next to a river or stream is stripped of its trees and vegetation.

- The logs are sold or used as fire wood in stoves to cook meals for the mine workers.

- After the area is cleared, a small pit is dug.

- Naturally, ground water wells up in the pit and the dredge is placed right then and there.

- The dredge has a tube and a pump, powered by a gasoline-guzzling generator. The tube, steered by people wading in the pit, sucks up water and soil, enlarging the size of the pit.

- The sucked-up sediment reaches a conveyer belt with a rough rug on it, a material that resembles Velcro. Large pebbles and sand roll off the conveyor belt while creating growing mounds right next to the pit.

- Tiny gold fragments are trapped in the rug on the conveyor belt.

- Every once in a while, the rug is taken off the makeshift belt and carefully placed in an old gasoline barrel.

- A bit of river water is added and miners jump into the barrel to stamp and jump out any residue, similar to the way they used to make wine. The rug is cleaned and the watery residue is boiled together with liquid mercury.

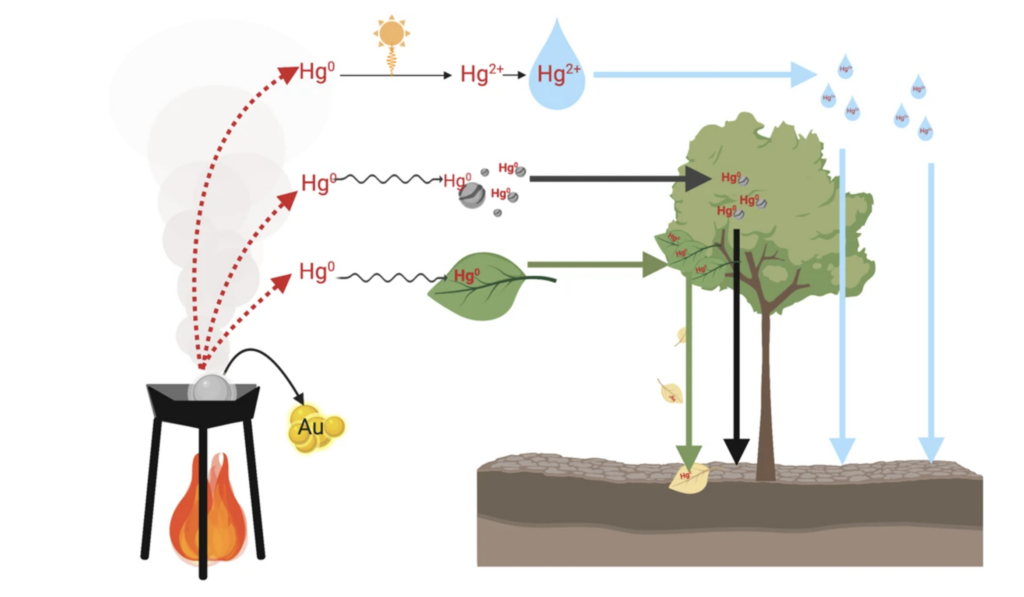

- The mercury makes the tiny gold fragments lump together, creating a little nugget and all excess water and sand burns and evaporates, as does a fair amount of the mercury itself. These chemicals do not disappear, they simply transform from liquids or solids into transparent gass.

- The gold is taken to the nearest town and sold for cash

- The machines dig another pit, and the rug is cleaned once again. The gold miners keep going, over and over, stripping out all the land’s organic matter and reducing the soil to simple sand.

The environmental effects of the gold mining practices in Madre de Dios take place on a physical, ecological and chemical level and have both short-term and long-term consequences.

Novel Ecosystems

Physically, the mining is creating novel ecosystems, by turning the natural forest and riverbeds into ponds and sand mounts. This alteration of the landscape has a tremendous effect on hydrology, water temperatures and sediment load. In a region with mines, you’ll find more murky water, warmed up in shallow ponds, and the rivers’ course is slowed down by sand mounts and deep pits.

These physical alterations have an effect on the natural ecosystem, as aquatic species that are adapted to rivers with a healthy riparian zone, cannot survive in a stagnant pond-like habitat without any vegetation. Apart from not being able to take the heat in their newfound murky ‘hot tub’, flowing water species need water to actually flow in order to absorb oxygen from the water and fulfill many other aspects of their life cycles, such as spawning and dispersing.

A novel habitat means that there are new niches to be filled by animals, plants and other organisms. For an ecologist this can be a rather exciting situation. A recent study shows that abandoned mining ponds have a large diversity of life in them. A surprise, since these ponds contain heavy metals, but the fish, invertebrate and plankton that this team found seemed unbothered by this cocktail. Surprisingly, the newly created wetland ecosystem with ponds rather than a smooth river bed, has species that would otherwise not be present in the natural ecosystem. There is an increase in biodiversity and as the cherry on top, the new species are an important food source for the rest of the food web too. So, maybe these mining ponds aren’t all bad?

Mercury pollution

The problem is that the ponds are filled with mercury and other pollutants. The chemical alteration of this ecosystem is a cause for alarm as some aquatic species do not seem to mind living in polluted ponds, but they do store the mercury in their cells which then gets into the rest of the rainforest food web, as they get eaten by fish, birds and humans .

Mercury pollution happens in two forms: as tiny particles in water and soil, and as atmospheric deposits, as this element evaporates really fast when used. A study that was published last month showed that intact forests in the Peruvian Amazon near gold mining receive extremely high inputs of mercury in the atmosphere, on canopy foliage, and in soils. The forests around gold mining intercepts large amounts of particulate and gaseous mercury, and there is a substantial mercury accumulation in soils, biomass, and in resident songbirds in some of the Amazon’s most protected and biodiverse areas. The authors righteously raise important questions about how mercury pollution may constrain modern and future conservation efforts in these tropical ecosystems.

The forest around the gold mines is absorbing mercury through precipitation and directly into the tree leaves resulting in mercury concentrations 15 times greater than surrounding deforested areas. This mercury load at Los Amigos exceeds previously reported mercury fluxes in forests of North America and Europe near coal combustion sites and is comparable with values in industrial China.

To comprehend the extent of this situation: ecologists who choose the remote Los Amigos Biological Station on the Madre de Dios, 5 hours upriver from the nearest town, in seemingly pristine rainforest, are performing their ecological research in a place where the average concentration of mercury was among the highest reported in the literature worldwide. The fact that the forest around the gold mines is absorbing mercury through precipitation and directly into the tree leaves (of which there are many) results in mercury concentrations 15 times greater than surrounding deforested areas. This mercury load at Los Amigos exceeds previously reported mercury fluxes in forests of North America and Europe near coal combustion sites and is comparable with values in industrial China.

Imagine studying wildlife that is neurologically and physically damaged, thinking it displays natural behavior. Shockingly, researchers found mercury concentrations in songbirds around Los Amigos that were 2−3 times higher than songbirds in an unaffected field site.

I start to feel a bit worried as I’ve spent a substantial amount of time in the Los Amigos Biological Station, drinking water from the local streams. But also, suddenly the locally obtained scientific data on animal physiology and behavior gets a whole new context to me. It is known that elevated mercury exposure in songbirds leads to reduced reproductivity, a decreased survival of chicks, increased physiological stress and mortality, and even alters behavior. Imagine studying wildlife that is neurologically and physically damaged, thinking it displays natural behavior. Shockingly, researchers found mercury concentrations in songbirds around Los Amigos that were 2−3 times higher than songbirds in an unaffected field site.

How long, and how diligent, have people been mining this region?

To myself, and many ecologists and conservationists with me, who visit this well-established Los Amigos Biological Station in the deep jungle, it is mind-blowing to realize that the station was actually built as a mining camp already 40 years ago. The features are clear: a broad, well-defined road that leads from the river port to the uphill station, used for trucks and heavy machinery, a big metal dredge lays abandoned in the jungle, and three sturdy cement dormitories. In 1982 these cement buildings were constructed by a Panamanian mining company. From 1983 to 1985, as many as 120 men lived in the camp, which they used as a base for gold explorations throughout the region.

This is just an example, to show that mining in Madre de Dios is not a recent development. A spectacular gold discovery occurred in the east of Peru during the summer of 1942, while the rest of the world was preoccupied by war. As the Amazon dry season progressed, word spread across the Andes that an important find had been made on the upper Río Negro and the gold rush began.

However, there are earlier discoveries of gold placer deposits in southeastern Peru by explorers Edmunds in 1890 and Conway in 1901. During the first real boom, the miners were mostly locals from Madre de Dios, although some people came from other parts of the country.

So, with this region being known for gold for a long time, I wonder how come the industry has exploded in recent years. A study in 2013 made a major stride in mapping the extent of the mining in this region. The scientists combined field surveys, airborne mapping, and high-resolution satellite imaging to assess road- and river-based gold mining in the Madre de Dios region of the Peruvian Amazon from 1999 to 2012. In this period, the geographic extent of gold mining increased 400%.

The average annual rate of forest loss as a result of gold mining tripled in 2008 following the global economic recession (from 2,166 hectares per year before 2008 to 6,145 hectares per year from 2008 to 2012).

The average annual rate of forest loss as a result of gold mining tripled in 2008 following the global economic recession (from 2,166 hectares per year before 2008 to 6,145 hectares per year from 2008 to 2012) and was closely associated with increased gold prices. At the time, and currently, small clandestine operations comprised more than half of all gold mining activities throughout the region.

More recently in 2020, The MAAProject, a project lead by the US non-profit Amazon Conservation and Peruvian NGO ACCA, mapped the expansion of deforestation due to mining, and concluded that a monthly 250 hectares of rainforest is lost to mining in Madre de Dios.

It dawns on me that with the surging global gold prices, combined with few other job opportunities in the region, it’s pretty logical that an increasing amount of people are choosing their bets in the mine.

What drives people to this destructive industry?

To get a personal insight on the ‘why?’-part, I speak to señora Lourdes Kalinowski. A motherly, older woman, who keeps telling me ‘not to worry’ while trying to set a specific time for a phone call. She worked as a chef in one of the mining camps, and is not afraid to share her story, while I figure out why people are drawn to work in this industry. Her testimony of her time in the gold mine, which lasted only one year, is one of strong morals and respect for nature.

In the year 2003, Lourdes started working in the gold mine, as there were a lot of job opportunities and many of her friends and family members had jobs in various mining concessions. As a woman, she had a set monthly salary, while the men were paid based on the monthly yield. The pay wasn’t bad and she needed to sustain her family. She stopped working for the mine after one year, as she realized the industry wasn’t legal, which caused her lots of concern.

‘It was a sad time. First of alI, I saw the destruction of the environment happening right in front of my eyes. Second of all, we were at risk of being evicted, or worse: bombed, by the military who were fighting illegal mining. The job itself was risky and unhealthy, so I didn’t want to continue.’

Lourdes Kalinowski

The fear of being bombed, working in harsh conditions with gasoline filled air and mercury-laced ponds, seems apocalyptic. But the ambience in the mining camp wasn’t a doomsday scenario: ‘The people working in the mine worked hard, but there was also time for relaxation. I think we had a good boss, these things differ per mining camp. Every Sunday, we would form teams to play volleyball or football, and we could go back to our village every other weekend. We didn’t work through the night, as nightly rest was very important to not have any accidents with the heavy machinery. I fed the workers with good meals and nice juices. We made sure to give the men plenty of rice, yucca, papaya and bananas.’

While Lourdes made sure to feed her coworkers with nutritious food, she did notice the toll the camp took on the camp staff’s health. Lourdes knows about the effects of mercury on the human body and is very aware that this pollutant ends up in the water and the fish that the miners eat. Besides the long-term effects that mercury has on human health, there were other short-term hazards. The men operating the machinery inhale gasoline fumes all day long. The women who manage the wood-fired stoves often get burned, and decent treatment is far away. Lourdes remembers that accidents with the dredging machines were common as the river rises quickly and uncontrollably.

“Working an illegal job means there is no formal contract, no job stability or security, no insurance in case of accidents, and fearing the government to drop a bomb on your camp. The government should create more job opportunities to stop people from going into this illegal industry, it’s a better solution than just bombing the camps and equipment.”

Lourdes Kalinowski

Of the 70 people in Lourdes mining camp, about 75% were male. There was a team to remove trees and vegetation, a team to collect firewood, a team to operate the machines, a team for new location scouting, and the 25% of women were divided into groups to cook, wash, and clean. Lourdes still has family members working in the mines, but stresses that the industry has changed and local people from Puerto Maldonado are not prone to work in the mines anymore. ‘Many of my friends and family that used to work in the mines, have changed to farm work, ecotourism, boat driving and transportation. Most people working in the mines nowadays are from Cusco or further away. It’s not a good job to have, and it makes me very sad to think about all the people that are forced to work in this illegal industry in order to support their family. Working an illegal job means there is no formal contract, no job stability or security, no insurance in case of accidents, and fearing the government to drop a bomb on your camp. The government should create more job opportunities to stop people from going into this illegal industry, it’s a better solution than just bombing the camps and equipment.’

Looking for a golden future

Even though I’m starting to understand people’s desperation and the decisions that come from it, it remains hard to ignore the massive ecological damage that continues to occur in the Madre de Dios rainforest. The surroundings of the riverbeds currently look like a gashing wound, but…things are changing.

In 2017 and 2018 deforestation from mining reached alarming rates with the deforestation of 18,440 hectares across southern Peru in just two years . The Peruvian government decided to take action in February 2019 with Operation Mercury. This operation used military forces to fight the illegal mining camps by recovering the principle of authority, and through large-scale reforestation.

At the start, SERNANP (Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado) was optimistic about its approach and seized the moment to plant a symbolic tree in the waste land. They foremost wanted to demonstrate that the productive and sustainable development of Madre de Dios is possible, based on its natural capital that includes the forest and also mining, as they worked on its formalization. Later, the mission turned grimmer, as the military only gave short notice before bombing camps and mining equipment and seizing all motorized vehicles.

However, the operation seemed successful as by the end of 2020, a 90% decrease of gold mining was observed in La Pampa through satellite imagery20. The operation was targeted at this most critical and expanded mining area where indeed miners seemed to have packed their bags. However, gold mining deforestation increased in three other key areas, indicating that some miners expelled from La Pampa moved to surrounding areas. The Peruvian government, however, has recently carried out major interventions in all three of these areas. Overall, gold mining deforestation decreased 78% across all six sites following Operation Mercury.

Illegal mining does persist, however. Since 2020, there is still documentation of 1,115 hectares of gold mining deforestation across all six sites since Operation Mercury (but, compared to 6,490 hectares before the Operation).

The abandoned gold mines are now being reforested with the help of local people. One of them is my friend, Karla Jurado, a young single-mother and a Puerto Maldonado native who usually works in tourist lodges across the region. Karla chose to work with SERNANP for the second phase of Operation Mercury, the reforestation phase. She found the call for workers on Facebook, and because there was no work in tourism due to the pandemic, she took her chances.

Karla says, ‘We knew of the pollution and devastation caused by gold mining in La Pampa, so we thought it was a good thing to do.’ She worked in La Pampa, in one of several reforestation camps, for 6 months straight. Ten days of labor and three days of rest, the transport to and from the reforestation zone was arranged and the camp conditions were basic. The pay was very limited according to Karla.

‘It was hard work. We were in the blazing sun, working on the sand flats, often plowing through heavy mud. We didn’t have any dangerous encounters with the illegal gold miners, but I heard of another reforestation camp that did. It felt dangerous to be working so close to people who do not care about the law and who didn’t necessarily support our efforts. The reforestation crew who came into conflict with the illegal miners eventually abandoned that zone.’

Karla Jurado

The planted trees, such as the large hardwood shihuahaco (Dipteryx micrantha), but also fruity trees such as achiote (Bixa orellana) and guava (Psidium guajava), were chosen based on their ecological and nutritional value. It’s debatable if planting fruit trees in mercury polluted areas brings more harm than good to the consumer, as leaves and plant tissues can absorb atmospheric and soil mercury, but optimistically, Karla was told that this was to ensure the return of wildlife. The reforestation program is still ongoing, as more surface needs to be reforested. Karla now keeps herself informed about the progress. ‘The trees are growing well, it’s going well. The Ministry of Agriculture is monitoring the results and shares this with the local public.’

While the first law to regulate gold commercialization was passed as far back as 1971, in recent years, a lot more effort is put into prosecution of illegal mining and a clear governmental guideline has been established for the formalization of small-scale artisanal gold mines. People need to comply with this guideline when they legalize their mining concession. It has strict rules on accident prevention and even demands a mitigation plan to leave the gold mine area behind with a minimized alternation of the natural ecosystem. If all needs of this guideline are met, the government will formalize and legalize the mine .

Local knowledge institute CINCIA (Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica), affiliated to Wake Forest University in the United States, has an ambitious scientific agenda around mercury-involved pollution. CINCIA seeks to generate scientific knowledge to allow for better decision-making in the region and communicates its findings to decision-makers and the community, democratizes knowledge, while generating opportunities for sustainable development.

To aid reforestation after mining, they established a network of 42 hectares of experimental plantations along an ecological and socioeconomic gradient covering the jungle of Cuzco and Madre de Dios. Simultaneously, to assess the health effects of mercury they generate scientific evidence to better understand the flow of mercury. To extract the mercury from polluted soils, they experiment with bio-carbon as a potential remediation tool. Bio-carbon can increase nutrient and water retention capacity in the soil, therefore improving acidity and stimulating the microbial functions of soil .

In addition to the government, universities and institutes, non-profit organizations are getting anxious to find solutions for Madre de Dios. The Amazon Aid Foundation has their mind set on creating awareness about these illicit gold practices and created The Cleaner Gold Network. This alliance of consumers, scientists, artists, educators, indigenous communities, NGOs, and companies from the gold sector, engage in a multi-initiative approach to promote solutions for unregulated gold mining in the Amazon. Their movie ‘River of Gold’ uncovers this industry with compelling images and stories.

Several years ago, the ACEER foundation brought clean gold experts to the region and started experimenting with an electroplating technique. Without burning mercury to lump gold fragments, this technique actually demonstrated a 3-4 increase in gold collection. Worldwide, various non-mercury techniques have been developed, but tradition, habit and cost makes the transition slow.

Besides creating awareness, great strides are made to transform gold mining into a less polluting process by using mercury-free practices. Several years ago, the ACEER foundation brought clean gold experts to the region and started experimenting with an electroplating technique. An electric current draws gold ions, which are positively charged, through a gold bath solution, allowing them to adhere to the negatively charged piece of metal. So, without burning mercury to lump gold fragments, this technique actually demonstrated a 3-4 increase in gold collection. The findings were presented to the public and members of the mining community. Implementing the technique was not very successful as the miners valued their tradition and found the electroplating equipment too costly, although they would have quickly redeemed the price given the increased yield. Worldwide, various non-mercury techniques have been developed, but tradition, habit and cost makes the transition slow.

A new surge of sustainable solutions is soon to come, as Conservation X labs, has opened up a Grand Challenge: the Artisanal Mining Challenge, Amazon edition. This technology and innovation company creates solutions to stop the extinction crisis, calls for any innovators, researchers, and entrepreneurs from all over the world to develop and implement solutions that address the environmental and social costs of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in the Amazon. Coming summer, various teams of innovators are going to test their solutions in the field, making the region a better place from an ecological and socio-economical perspective.

To extract from all the people I’ve met that are working in, with and against illegal gold mining, I think the future for the rainforest is bright. If all laws, ideas and solutions are put to the test and implemented, this piece of the planet will be able to get ecologically restored and thrive once again.

I’ve got my answers on the why here, why now, why them and how the river and forest are affected. My quest has led to more questions about the illicit world that came with the invasion of illegal gold mining, which I will explore soon in another blogpost. To extract from all the people I’ve met that are working in, with and against illegal gold mining, I think the future for the rainforest is bright. If all laws, ideas and solutions are put to the test and implemented, this piece of the planet will be able to get ecologically restored and thrive once again. You can come and float around on a river of gold, without hearing the sound of pumping dredges, or smelling the smell of gasoline, or seeing murky ponds and sand heaps next to the river. This region is worth a happy ending, and a healthy river is part of that.

Resources

1 Matthias Willbold, Tim Elliott, Stephen Moorbath. The tungsten isotopic composition of the Earth’s mantle before the terminal bombardment. Nature, 2011; 477 (7363): 195 DOI: 10.1038/nature10399

2 Gérard Hérail, Michel Fornari, Michel Rouhier. Geomorphological control of gold distribution and gold particle evolution in glacial and fluvioglacial placers of the Ancocala-Ananea basin – Southeastern Andes of Peru. Geomorphology, 1989, Volume 2, Issue 4.

3 Villegas, C., Weinburg, R., Levin, E., & Hund, K. (2012). Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in Protected Areas and Critical Ecosystems Programme. World Wildlife Fund for Nature.

4 GlobalData’s mining database, 2020.

5 Statistica, 2020, Distribution of gold mine production in Peru in 2020, by region.

6 LePan, Nicholas (2021). “Visualizing Global Gold Production by Country in 2020”

7 World Gold Council, 2021. https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/historical-mine-production

8 USAID, Case study: artisanal and small-scale mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. October 2020

9 Weinhouse, Caren, John A Gallis, Ernesto Ortiz, Axel J Berky, Ana Maria Morales, Sarah E Diringer, James Harrington, et al. 2020. “A population-based mercury exposure assessment near an artisanal and small-scale gold mining site in the Peruvian Amazon.” Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology

10 GIATOC. (2017). Case Study: Illicit Gold Mining in Peru. Geneva: Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime.

11Abe, C. A. et al. Modeling the effects of land cover change on sediment concentrations in a gold-mined Amazonian basin. Reg. Environ. Chang. 19, 1801–1813 (2019).

12 Dethier, E. N., Sartain, S. L. & Lutz, D. A. Heightened levels and seasonal inversion of riverine suspended sediment in a tropical biodiversity hot spot due to artisanal gold mining. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 23936–23941 (2019).

13 Julio M. Araújo-Flores, et al. Seasonality and aquatic metacommunity assemblage in three abandoned gold mining ponds in the southwestern Amazon, Madre de Dios (Peru), Ecological Indicators, Volume 125, (2021)

14 Feingold, Beth J, Axel Berky, Heileen Hsu-Kim, Elvis Rojas Jurado, and William K Pan.. “Population-based dietary exposure to mercury through fish consumption in the Southern Peruvian Amazon.” Environmental Research (2020)

15 Gerson, J.R., Szponar, N., Zambrano, A.A. et al. Amazon forests capture high levels of atmospheric mercury pollution from artisanal gold mining. Nat Commun 13, 559 (2022).

16 Ackerman, J. T. et al. Avian mercury exposure and toxicological risk across western North America: A synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 568, 749–769 (2016).

17 Pitman, N. An overview of the Los Amigos watershed, Madre de Dios, southeastern Peru, April 2015.

18 Alan K. Graig. Placer Gold in Eastern Peru: The Great Strike of 1942.

19 Asner et al., Elevated rates of gold mining in the Amazon revealed through high-resolution monitoring. PNAS November 12, 2013 110 (46) 18454-18459; (2013)

20 Maap #130: illegal gold mining down 78% in peruvian amazon, but still threatens key areas. 2020, Amazon Conservation.

21 Business Today, 2022

22 Maap#96: gold-mining-deforestation-at-record-high-levels-in-southern-peruvian-amazon, 2019, Amazon Conservation

23 SERNANP noticias, gobierno Peruano, 2019

24 Fay, L. & Gustin, M. Assessing the influence of different atmospheric and soil mercury concentrations on foliar mercury concentrations in a controlled environment. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 181, 373–384 (2007).

25 Guia para la fiscalización ambiental a la pequeña minería y minería artisanal, MINEM, 2019.

26 Tollefson, J. The scientists restoring a gold-mining disaster zone in the Peruvian Amazon, Nature 578, 202-203 (2020)

27 CINCIA, Mercury Program, 2021

28 Thermo fisher, electroplating technique