Judith Westveer

Scientific Journalist

I am a creative academic who likes to tell stories about nature, and the Amazon rainforest is my biggest source of inspiration. After finishing a PhD in Conservation Ecology, during which I studied ways to protect and restore wetlands, I worked for several Peruvian environmental NGO's. Currently, I'm focused on creating awareness on the importance of nature.

Learn more about Judith Westveer

November 4, 2022

Living with Wildlife: from subsistence hunting to international wildlife trafficking

‘The smell hits you like a train. Burned hair, rotting flesh, and old meat that’s not smoked for flavor but for necessity. Anyone who is solely used to eating western food, would doubt to eat anything there.’ – is how Dr. Brian Griffiths, researcher of hunting traditions and game species in the Peruvian Amazon, describes his visit to a ‘wet market’ in Iquitos, Peru. Iquitos has about seven of these wet markets: an open-air bazaar that sells meat, all sorts of it, as well as live animals for food, pets and shamanistic rituals. ‘What smelled the worst were actually the chickens. Only if I was truly desperate would I buy chicken. The meat is prone to have viruses and bacteria, so it’s logical to resort to other types of meat, including bush meat.’

Well, there is an image you won’t be able to forget soon and which differs in every single way from your usual Western supermarket outing. But for the people in Iquitos, as well as in many South-American, African and Asian countries, these markets provide a main source of protein and a way to make an income. They are also a hub for disease and wildlife trafficking.

Belen Market in Iquitos, Peru | Photos: Therany Gonzales

Brian continues to set the scene: ‘Vendors sell fish on one row, meat on another, fresh or smoked. The carcasses are spread out, headless, left with the skin on but the hair burned off, usually ridged with slices, smoked and salted.’ To preserve the recently hunted game meat, hunters immediately gut the animal in the field, eat the perishable parts, and then salt and smoke it before selling it to a middle man or a market. ‘The most common meats I found on the market in Iquitos were collared peccaries (Dicotyles tajacu), paca (Cuniculus paca) and deer (Mazama americana), but one can find woolly monkey meat (Lagothrix lagotricha), tapir (Tapirus terrestris), agoutis (Dasyprocta variegata), caiman and tortoises. The tortoises are often sold alive and killed right in front of you, after choosing between a whole, a half or a quarter tortoise.’

While we know that people have been hunting for millennia, what exactly is the magnitude of bushmeat hunting in the Peruvian Amazon and which species are mostly sought? What proportion of captured rainforest animals end up in the illegal pet trade? Is there any way to keep the wildlife alive in the wild?

Let’s dive deeper into the world of subsistence hunters and wildlife traffickers.

Shooting for survival

Peru is home to many Indigenous Peoples still practicing their traditional culture. In 2017, the 5,972,606 Indigenous peoples formed about 26% of the total population of Peru, distributed among about 55 ethnic groups of which Quechua is the largest. Most of these Indigenous communities are to some extent self-sustaining, meaning that they grow their own crops and tend their own livestock, in order to have sufficient food for their families to live off. Some communities herd alpacas in the chilly Andean Highlands and some communities hunt for game meat in the hot and humid Amazon rainforest. They are allowed to do this by law, as this is what’s called ‘sustenance’ or ‘subsistence’ hunting, literally ‘hunting to survive’. It is part of their cultural tradition and their livelihood, as long as it takes place on land that belongs to the community.

There are also protected areas in Peru that do not allow hunting, such as National Parks, National or Historical Sanctuaries and Wildlife sanctuaries. Hunting in these designated areas is by default illegal. However, in national reserves and protected forests, the use of natural resources (aka hunting and logging) is allowed to a certain extent, often by obtaining a permit first. Besides these categories, Peru actually has two designated Hunting Reserves, covering a total area of 124,735.00 hectares.

On private property, anything goes in terms of hunting, but people need a proper license to own a gun.

If hunting is only allowed for specific purposes and in restricted areas, then how come so much meat ends up at the market? After feeding the family, and gifting meat to the elders and leaders, apparently some hunters still have meat to sell. This can’t really be called subsistence hunting anymore, so should this be categorized as commercial hunting? Numbers on excess and illegal hunting are hard to find, but definitely happens in the dense jungle where individual hunters are hard to trace.

Overhunting can pose a serious threat to biodiversity. A meta-analysis of 176 studies on hunting and animal populations across the tropics, showed a decline of 58% in birds and of 83% in mammal abundances in hunted compared to non-hunted areas. Bird and mammal populations were depleted within 7 km from hunters’ access points (roads and settlements). Additionally, hunting pressure was higher in areas with better accessibility to major towns where game meat could be traded.

Overhunting can pose a serious threat to biodiversity. A meta-analysis of 176 studies on hunting and animal populations across the tropics, showed a decline of 58% in birds and of 83% in mammal abundances in hunted compared to non-hunted areas.

Besides a threat to biodiversity, hunting and direct contact to wildlife can cause problems for humans. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that wildlife markets should be seen as a major human-health risk. Another recent publication, using a dataset of 45 years, showed that game meat sales in Iquitos increased at a rate of 6.4 tons per year, paralleling urban population growth. Game meat sales were highest in 2018 (442 tons), contributing US$2.6 million (0.76%) to the regional gross domestic product. Five species of ungulates and rodents (collared and white-lipped peccary, grey and red brocket deer, paca) accounted for 88.5% of the amount of biomass traded. Vulnerable and Endangered species represented 7.0% and 0.4% of individuals sold, respectively. Despite growth in sales, the contribution of game meat to the overall urban diet was constant: 1–2% per year of total meat consumed. This result was due to greater availability and higher consumption of cheaper meats (e.g., in 2018, poultry was 45.8% cheaper and was the most consumed meat) coupled with the lack of economic incentives to hunt game meat species in rural areas.

The authors of both above-mentioned studies call for urgent strategies to sustainably manage game meat hunting in both protected and unprotected tropical ecosystems to avoid further declines in animal populations.

If subsistence hunting is done for the sole purpose of survival, and under certain conditions, it can be a way of sustainable game meat hunting. A well-known example is the Indigenous Matsigenka (or Machiguenga) population residing in Manu National Park in Peruvian Amazonia. Their main prey species are woolly monkey (Lagothrix lagotricha), spider monkey (Ateles chamek), white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), Razor-billed Currasow (Mitu tuberosa), and Spix’s Guan (Penelope jacquacu). Researchers found that there was little or no evidence that any of these five species had become depleted in Manu National Park and there has been little change in per capita consumption rates or average prey weights, despite a near doubling of the human population since 1988.

The current hunted meat quantity by the Matsigenka appears to be sustainable for the surrounding wildlife populations, because of four reasons:

- First, while hunting is allowed in Manu, it is also heavily regulated. The government controls the use of shotguns and the Matsigenka still hunt with bow and arrow. This limitation on technology controls hunting success, as only certain species can be effectively killed with an arrow, and even a well-trained bow hunter can only take so many animals per day.

- Second, hunting animals at one site, but leaving other sites untouched, creates a source-sink dynamic where large populations from the ‘source’-sites (non-hunting) spill over in the ‘sink’-sites (hunting). Source-sink dynamics imply that even with continued human population growth within a settlement animal populations can counterbalance this with population growth.

- The third and fourth conditions for sustainable hunting are that there is no habitat destruction in the hunting area and that the hunting area isn’t expanded.

What does the hunter hunt?

Dr. Brian Griffiths has seen from his studies that there is a clear pattern in where and what the hunter hunts, which likely does affect the animals’ populations, at least locally. ‘Hunters gear their hunting efforts towards consumer preference. The region where I do my research has a ton of tapirs in the forest, but since tapir meat isn’t popular on the market, the hunters generally do not opt for shooting tapirs.’

Which animal does get shot, is determined by a couple other elements too:

- the persons’ hunting skills (are we dealing with an insecure beginner or a forest veteran?)

- certain landscape parameters (dense understory vegetation, hilly terrain, crossing rivers?)

- prey features (swift movements, perfectly camouflaged?) and…

- pride. No one wants to return to their family empty handed, so if too much time passes by, maybe that slow large tapir is just what’ll do for the day.

In addition to economic value and hunting skills, certain animals are selected or avoided for other reasons: ‘Some hunters have specific personal and cultural beliefs, for example, eating woolly monkeys was traditionally associated with masculinity, and was often served during weddings. On the contrary, howler monkeys, and red brocket deer are associated with evil spirits in many cultures and are best to be avoided. Similarly, it is believed that sloth meat makes people lazy.’ – says Griffiths, who has spent years studying hunting practices of Amazonian Indigenous communities and living in one community. Besides attributing specific characteristics to the animal itself, some areas in the rainforest can be associated with dangerous spirits, so no one hunts there. These off-limit hunting areas could potentially be a regeneration refuge for the rest of the animal population.

Although meat is the most frequently sold wildlife product on wet markets, they also sell wild animals as pets, animal parts for spiritual use, traditional medicine, and decorative use.

Although meat is the most frequently sold wildlife product on wet markets, they don’t thrive solely on meat sales. These markets also sell wild animals as pets, animal parts for spiritual use, traditional medicine, and decorative use. Has Griffiths ever seen live animals at the market in Iquitos that were not sold for food? Oh yes; flocks of caged wild parakeets, clinging and screaming baby monkeys, and even an ocelot in a tiny enclosure, ready to be sold to the highest bidder.

Trafficking, seizing and rescuing

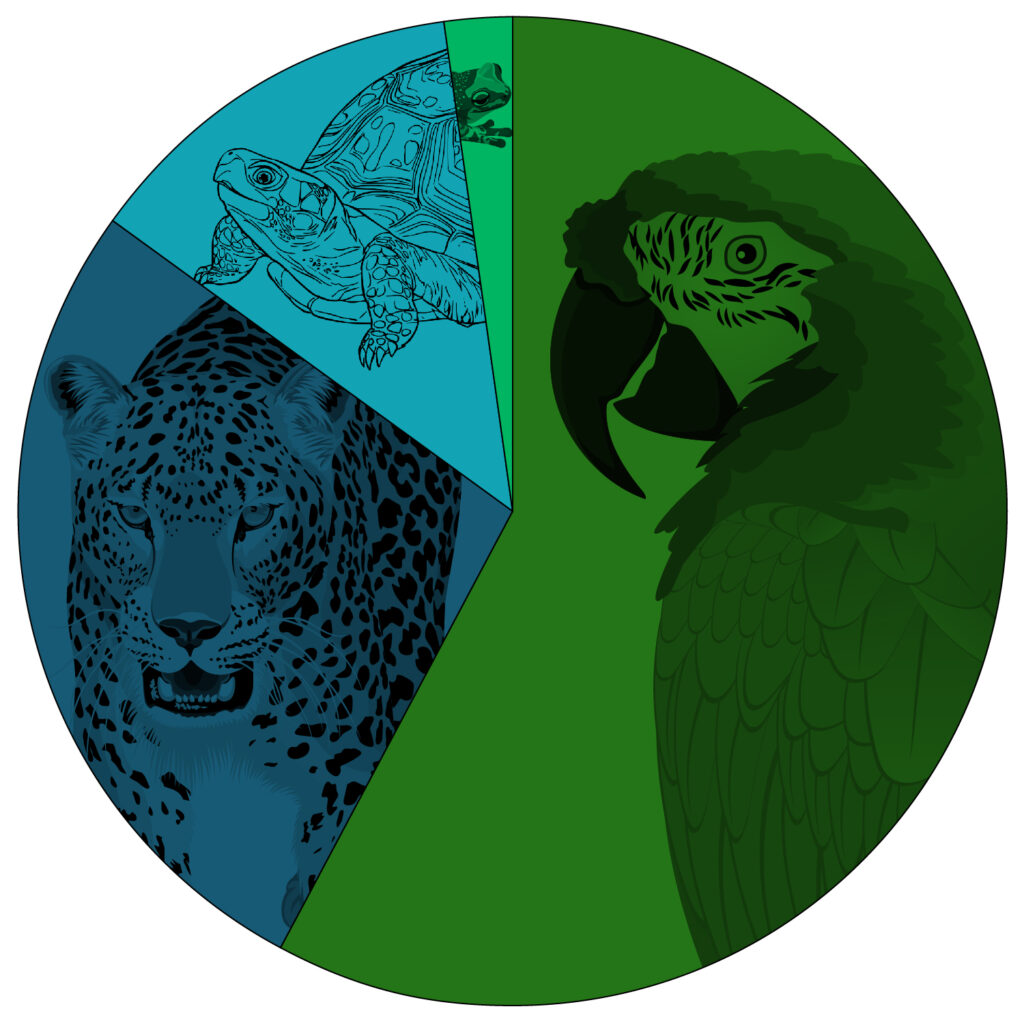

Wildlife trafficking is Peru’s third biggest illegal industry, after drugs and weapons, and driven by national and international consumer demands. With more than 318 different species confiscated between 2000 and 2015, it’s not surprising that Peru is recognized as one of the most active exporters of live wild animals worldwide. Of the species confiscated by SERFOR, the National Forest and Wildlife Service, 58 percent were birds such as parrots and parakeets, 27 percent were mammals such as monkeys and cats, 13 percent were reptiles such as river turtles and tortoises, and 2 percent were amphibians such as the rare Titicaca and Junin frogs.

Wildlife trafficking is Peru’s third biggest illegal industry, after drugs and weapons, and driven by national and international consumer demands.

Of the 318 species, 151 are listed on the Appendices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). These animals and animal parts are for local and international markets, with the main destinations including Asia, Europe, and North America, although Peru itself is by far the largest market.

Some of the trafficked animals end up with the client, some of them die during transportation, and some are seized by authorities. Between 4,000 and 5,000 individuals of protected wildlife are rescued alive annually in the country by SERFOR. The animals that are seized, the ones that survive, need a new home. SERFOR and OSINFOR (Forest Resources and Wildlife Supervision Agency) are in direct contact with several rescue shelters around the country and bring seized animals over on a regular basis. One of these places is the conservation center Hoja Nueva in Madre de Dios, translated ‘A new leaf’, run by conservationist and scientist Samantha Zwicker.

Hoja Nueva

‘Hoja Nueva started as a research and community center on the Las Piedras River, and it wasn’t until a couple years later that we started doing wildlife rescues. In 2018, we received an emergency message from a member of a nearby river community about an ocelot.’ – says Samantha. At that time, loggers were passing downriver and stopped to rest in the community. They had a few dogs with them and had captured the ocelot – a small wild cat.

Photos from Hoja Nueva Social Media and website

Samantha’s team rushed to the community to find the baby ocelot wandering the floor of one of the community stores. Someone had taken him from the loggers, knowing that the wild animal probably had a better future with Samantha. ‘The existing local rescue centers were mainly focused on primates or large mammals, but didn’t have a rehabilitation program for felines, and because we believed that these cats had a future in the forest, we took on the challenge.

In 2020, we developed a specific center for wildlife rescue at a different location from the established research station, and were able to rescue a larger quantity and variety of animals, specializing in felines and reptiles. Visitors are not allowed at the rescue center, since its purpose is to actually rehabilitate the animals to live in the wild again. To keep the center running, we use the income from our research station that hosts visitors, scientists and volunteers.’

Basically, all animals that end up at Hoja Nueva are victims of the wildlife trade. They are brought to Samantha and her team by the local authorities after they seize the animal, or after shutting down local zoos when animal welfare conditions are too poor. Most animals that reach the rescue center come in mistreated, neglected and malnourished, and while the early years of the rescue program at Hoja Nueva involved local victims, they now receive felines from all over Peru, as far as Iquitos.

‘Sometimes we are contacted directly by local communities, to take an animal that they thought would make a good pet. In Madre de Dios, we don’t see a lot of large-scale organized wildlife trafficking, as they seem to have up north in Iquitos. Most people that sell live animals are opportunistic; they occasionally bring back an animal after hunting. On the one hand, there are people that, for example, come across a nest that they think is abandoned and want to help, so they take the juvenile back to the village to keep as a pet. Other people know that the business is lucrative. They shoot the mom for meat, and sell the baby.’

Samantha thinks that a key approach to decreasing and preventing wildlife trafficking is to give the local, regional and national government more power to act. ‘I see a lot of NGO’s doing the actual legwork when an animal needs to be rescued, but it would make a huge difference if the responsible governmental departments would receive more funding in order to respond quickly. For example, if they would have immediate access to a car or truck to help with the rescue and liberation of captured animals, it would be a massive change for all partners involved.’

She says that awareness campaigns have been successful to a certain extent, but that a clear top-down approach is necessary: ‘Although we have biweekly contact with the governmental departments of SERFOR and OSINFOR, there is lots of staff turn-over, which makes working together on long-term projects difficult.’ Luckily, the three big local rescue shelters in Madre de Dios, Hoja Nueva, The Amazon Shelter and Taricaya, are coordinating and communicating regularly and are also supported by UPA, a non-profit organization that creates awareness on animal welfare and trafficking.

Teeth, skins, and bones

Dry skin, frizzy hair or bad luck? Many animal parts are considered to have spiritual or medicinal healing properties. Interviews with Indigenous peoples revealed for example, that wrapping the skin of an anaconda around a pregnant woman’s abdomen is supposed to help with safe childbirth, deer legs are said to help children that have difficulty walking, a toucan’s beak is said to induce love, drinking opossum’s blood is said to cure asthma and a coati’s penis is used as an aphrodisiac. These traditions and beliefs lead to trade, and local markets sell animal parts for these purposes. Although the exchange of animals and animal parts also happens clandestinely inside the villages.

One animal group that is infamously popular for its body parts are the wild cats.

One animal group that is infamously popular for its body parts are the wild cats. Confiscations of hundreds of jaguar heads and canines in Central and South America from 2014 to 2018 resulted in worldwide media coverage suggesting that wildlife traffickers are trading jaguar body parts as substitutes for tiger parts to satisfy the demand for traditional Asian medicine. It is thought that the increase of illegal jaguar products is potentially a side effect of a stronger economic partnership between Central and South American countries and China.

But it’s not just traditional medicine that leads to a high demand for cat parts. Several spotted-cat species populations in Latin America, including the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii), and jaguar (Panthera onca) have been impacted due to the international trade of skins, especially for the fashion industry in Europe and North America in the 1960s and 1970s.

The ocelot and the jaguar were the most exploited species for their skins in the pre-CITES period (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora since 1975), as well as post-CITES, although at significantly lower levels. Post-CITES trade, however, still shows an increasing trend for the jaguar and all wild cat species but for other illegal purposes.

The connection between Asia and South-America is hard to ignore when it comes to the trade of wildlife, as in 2020, another investigation by Earth League International and the Dutch national committee to the IUCN revealed that Chinese-controlled trafficking syndicates are responsible for smuggling jaguar body parts out of Bolivia. These groups hide behind legitimate businesses like restaurants and shops, which also serve as fronts for the transit of other wildlife and illegal drugs, the investigation found.

In an interview with Mongabay, a smuggler revealed that the most common method to transport jaguar parts such as teeth, bones and even genitalia is simply by air. ‘To get to [China], arriving directly by airplanes is avoided. It is preferred to stop at airports with less security,’ This transfer can take place in at least two ways: through a logistics chain that allows illegal goods to be hidden in legal shipments, or through people who carry fangs in their carry-on bags and even on their bodies. The interviewed smuggler adds that ‘they find the locations with the least resistance. If they need to move goods from Bolivia to Peru because it will be easier, they will cross the border to do it.’

How can we prevent hunting and trafficking?

Just like any illegal industry, getting a correct and complete impression on what is happening where, is very complicated. However, the legal international framework to protect wildlife exists – it was established in 1975 and is called CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. This international framework works to protect certain species against over-exploitation through international trade. It does not define wildlife crime as such, but it strongly influences national legislation on wildlife crime, and provides a means for international cooperation against trafficking. Parties of CITES are required to “penalize” illegal trade, which may include the criminalization of serious offenses.

The legal international framework to protect wildlife exists – it was established in 1975 and is called CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

CITES is important because wildlife protection laws usually need cross-border environmental legislation. Additionally, since wildlife populations are dynamic, most wildlife related legislation need regular updates from the government to issue regulations determining when and how wildlife can be harvested. Species can be added and removed from protected species lists, licenses issued allowing the legal taking of wildlife, and quotas established to ensure sustainability. As a result, the domestic legality of any given wildlife product is a matter of considerable complexity.

One of the functions of SERFOR (Forestry Department)—attached to the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI)— is to implement the ‘National Strategy to Reduce Illegal Wildlife Trafficking 2017-2027’ together with other institutions and public and private organizations. A 10-year national action plan was created, in order to carry out a series of activities and tasks that seek to progressively reduce the illegal trafficking of wildlife throughout the country. The strategy has three main objectives:

- Educate, raise awareness and disseminate information to the general public on illegal wildlife trafficking.

- Develop conditions for the strict application of the law and the effective control of the illegal wildlife trade wild in Peru.

- Implement alliances with bordering countries and destinations of illegal wildlife from Peru.

With 5 years left to complete this national strategy against wildlife trafficking, let’s look at what has been accomplished. Directly after installing the strategy, SERFOR combined forces with WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society) by using more than 10 years of government data, along with new research and surveys among Peruvians, to develop a social media campaign to raise awareness about the issue of wildlife trafficking in the country. Surveys demonstrated that a majority of Peruvians were not familiar with laws restricting the wildlife trade, so Facebook was used to launch the campaign, reaching over 250,000 people in the first month alone. Messages ranged from “2,000 birds can be sold illegally in one day” to “They kill the moms, so they can sell their young,” a reference to poachers’ method of capturing baby animals for the pet trade.

Besides a Facebook and Twitter campaign, efforts were put into the launch of several websites containing information and footage on wildlife trafficking. All websites are strongly calling for action: ‘If we Peruvians stop buying wild animals of illegal origin, we will put an end to trafficking. Do not be an accomplice of this crime, promise not to buy wild animals’, and clearly state what the legal and environmental consequences are of wildlife trafficking. SERFOR’s website has posters and documents publicly available for downloading and printing, to increase information spread to the general public.

In terms of stricter law enforcement, a first step was made by broadcasting the punishments for wildlife trafficking on the SERFOR websites and in social media campaigns – ‘Law No. 29763, Forestry and Wildlife Law, determines that buying and selling wild fauna of illegal origin is a crime, which can be punished with imprisonment and with the payment of fines that are greater than S /. 40,500.’ (approx. $11,000).

But SERFOR also cooperated with The Global Law Alliance for Animals and the Environment, as they conducted a workshop to combat wildlife trafficking with Peruvian officials. The ABA (American Bar Association) Rule of Law Initiative has collected the results from the workshop into a “Handbook for Strengthening the Fight Against Wildlife Crimes.” The handbook contains a series of practice pointers for Peruvian investigators, prosecutors, and judges working on cases involving wildlife trafficking. Some of their main conclusions were that Peru’s auxiliary legislation could be stronger, Peru should modify parts of the law in order to include all wildlife trafficking offenses, increase criminal sanctions and/or elimination of inconsistent penalties, clarify the laws around the possession of imported and/or illegally obtained wildlife, and identify mechanisms to strengthen the participation of SUNAT (Superintendencia Nacional de Aduanas y de Administración Tributaria) officials in the fight against wildlife trafficking. It is unclear at this moment if recommendations from the ABA Handbook are implemented by SERFOR.

Furthermore, alliances have been established with other countries to increase the control of potential illegal wildlife shipments. In 2014, the United States proposed the setting up of an international enforcement operation targeting illegal wildlife trade, and encouraged Members from South and North America, as well as Europe, to participate. The proposal was fully supported and the operation, code-named FLYAWAY, was run from February to July 2015 with 14 Customs administrations participating, i.e. Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela and the US, as well as Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

The participation of OSINFOR and SERFOR was essential to ensure that controlled products were covered by a title document that had been verified or checked, and found to be in conformity with national legislation. In coordination with these government agencies, Peru Customs carried out operations in primary areas, such as airports, land terminals and border control posts, and in secondary areas, such as highways and at specific establishments.

Operation FLYAWAY revealed or confirmed the use of certain types of fraudulent practices, such as declaration of animals as being dead when they were actually alive; exports of unauthorized specimens among authorized specimens; exports of quantities greater than those authorized; exports to destinations other than those indicated on the permits.

Keeping the wildlife wild

Removing an animal from the forest where it belongs will have a certain effect on the animal’s livelihood, the remaining population and ultimately the entire ecosystem. The COVID-pandemic has shown us that living too close to wildlife and by consuming wild animals, human health can be jeopardized directly, but decreasing biodiversity with unsustainable hunting will also affect human welfare indirectly. Each organism has a place and a function within a healthy ecosystem, which is not in a tiny indoor-cage or ground up into a powder.

However, after investigating this topic for this blog, I see that there is a big difference between the effects of subsistence hunting by local communities, which can have minimal effects on wildlife population sizes, and large-sale international wildlife trafficking where massive amounts of wildlife are transported dead or alive across the globe for a greedy someone to have a leopard dress, a showy new lizard, or a storied medicine for impotence.

Both top-down law enforcement with strict controls and large punishments and bottom-up awareness campaigns to educate the consumer should be implemented in full force. Where there is demand for wild pets and animal parts, there will be supply. Let’s stop this demand and supply and keep the wildlife wild.

thank you for the article