Judith Westveer

Scientific Journalist

I am a creative academic who likes to tell stories about nature, and the Amazon rainforest is my biggest source of inspiration. After finishing a PhD in Conservation Ecology, during which I studied ways to protect and restore wetlands, I worked for several Peruvian environmental NGO's. Currently, I'm focused on creating awareness on the importance of nature.

Learn more about Judith Westveer

April 26, 2023

The origin of cocaine – a survival of the fittest

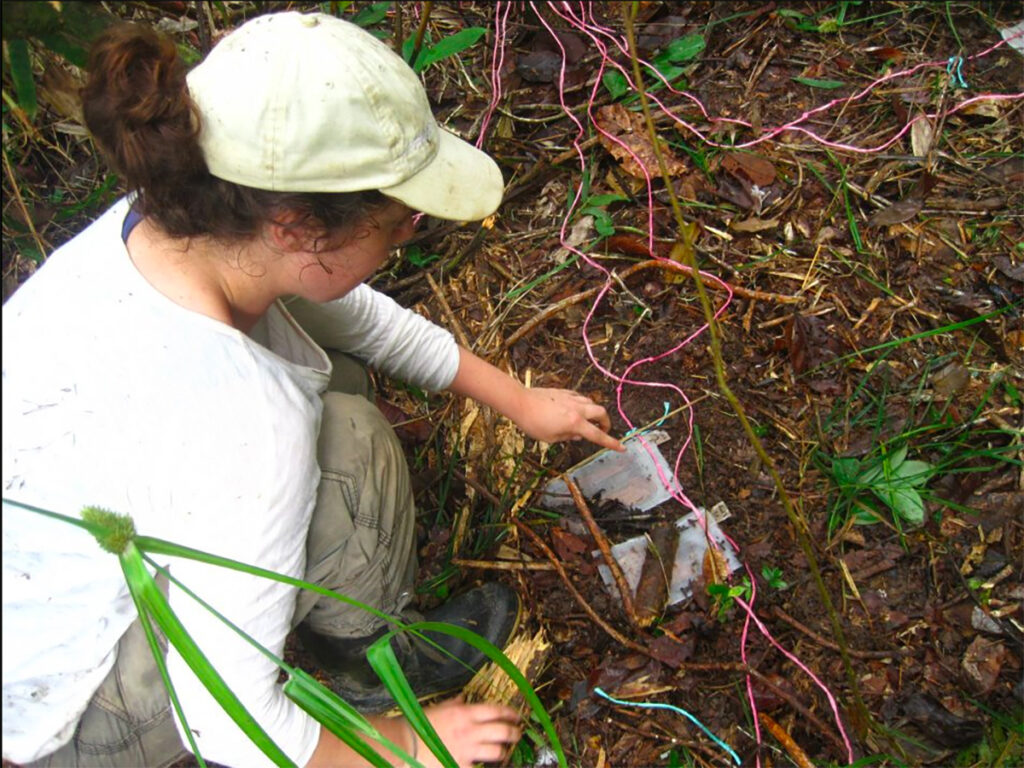

Years ago, I spent a long hot summer in a tropical rainforest studying the effects of agriculture on soil health, when something happened that I’ll never forget.

My whereabouts were in a tiny jungle village that wasn’t even properly visible on Google Maps. It didn’t take long before I knew everyone in the village, which consisted of only about 15 houses, most of them abandoned. Sometimes I would hear small airplanes fly over at night, very low to the tree cover, which seemed odd as there was no airport anywhere nearby and most of the village families were struggling to afford a boat, let alone own a private plane. One day, I was chatting to a neighbor when we heard a loud ‘PANG’, somewhere inside the nearby forest. My naïve-self disregarded it as a child playing with fireworks, but my neighbor responded very differently. ‘Go back into the house right now, and stay there for a while, don’t talk to anyone you don’t know.’ Seeing her visibly shaken up and scared to the bone, I realized it couldn’t have been mere fireworks, and hopefully it did not involve a child.

The next day we spoke again and she told me about the ‘narcotraficantes’, drug traffickers, and how they would sometimes come to the village to deal with ‘unfinished business’. Murder, threats and overall anxiety is what they brought. She pointed at the abandoned houses and mentioned the names of the families that once used to live there. All dead, or left in a hurry to escape from the drug lords, when they couldn’t provide the product or pay a debt that they were forcefully supposed to deliver.

Coca consumption has its origins in the ancient Inca tradition, but the scale at which it is used now has nothing to do with beautiful rituals anymore. It causes deforestation, contamination and violence.

Coca consumption has its origins in the ancient Inca tradition, but the scale at which it is used now has nothing to do with beautiful rituals anymore. It causes deforestation, contamination and violence. How can people and the planet survive this destructive industry?

Where does coca and cocaine come from?

In a thriving rainforest, plants need protection from herbivores such as insects, sloths, deer and alike. Hence, plants protect themselves with a bitter-tasting substance – alkaloids. Cocaine is one of the alkaloids in the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca), fending off hungry herbivores for the plant and acting as a stimulant and painkiller for humans. Therapeutically, alkaloids are particularly well known as anesthetics, cardioprotective, and anti-inflammatory agents.

The coca plant resembles a blackthorn bush and measures about 3 meters in height. It naturally grows in the valleys and upper jungle regions of the Andean region in western South America. The plant likes hillsides where it’s warm and sunny during the day and cold during the night. The countries of Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia together cultivate more than 98 percent of the total coca crops.

The countries of Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia together cultivate more than 98 percent of the total coca crops.

While Peru was the largest producer of coca in the year 2012 and 2013 (respectively 60k and 50k hectares of coca crops), Colombia held the largest numbers of coca bush before 2012 and since 2014. The estimated peak height of illicit cultivation was in 2017 with 171 thousand hectares of coca in Colombia. The eastern slopes and foothills of the Andes continue to be the principal source of Peruvian coca leaf. In particular, the valley of Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro rivers (in Spanish: Valle de los Ríos Apurímac, Ene y Mantaro), also known as the VRAEM, contained 88% of the UNODC estimated hectares of Peruvian coca surface.

These data are provided by the UN office on drugs and crime (UNODC), which has all sorts of beautiful excel sheets, graphs and maps available on drug cultivation, use and trade worldwide, if you click here.

Old and new coca traditions

Where the tradition of coca consumption exactly started is hard to tell – organic items such as plant leaves usually don’t get retrieved from archeological sites. However, it is a known fact that coca played a key role within the Inca empire. Information from early transcripts tell that coca was the most important plant offering during public rituals and important landmarks within the Inca domain regularly received offerings of this precious leaf. Besides offerings and chewing coca themselves, the Incas would put coca leaves in the mouths of mummies. Several leaves were recently found in the northern part of the Ayacucho Valley, which based on ceramic stylistic grounds, date to sometime between the end of the Early Intermediate Period (ca. 1–550 CE) and the beginning of the Middle Horizon Period (ca. 550–1100 CE).

It’s not clear how many people chew coca nowadays, but a study from 2004 estimated that over four million Peruvians continue to practice traditional use of the coca leaf. Coca leaf chewing can alleviate hunger, cold and fatigue and is used both in traditional medicine and shamanic practices. Traditional and limited use of the coca leaf appears to have no negative consequences while the sharing of leaves and participation in group sessions of coca chewing continues to create and strengthen ties between friends and family.

Once made into readily transportable cocaine, the drug is moved at less cost and risk to North America and Western Europe, the two regions estimated to consume over 70% of global cocaine.

Apart from chewing coca leaves, there is an ever-increasing global demand for coca paste and cocaine. Coca paste is mostly used locally by farmers and processors, or by low-income people. The distillation of coca paste into cocaine hydrochloride requires another step often undertaken in laboratories that reduces the volume and increases it significantly in value. Once made into readily transportable cocaine, the drug is moved at less cost and risk to North America and Western Europe, the two regions estimated to consume over 70% of global cocaine.

Not just any cash crop

Coca cultivation and transportation isn’t just like any other cash crop – it comes with severe and violent consequences, which were experienced firsthand by my good friend Natalia Campana. Natalia was born in 1986, in the Junín province of Peru, a paradise for coca plantations.

Her parents, from Lima, didn’t want their children to grow up in the big city and decided to make a living in agriculture, just like many Peruvians in the seventies and eighties. They bought a chunk of land and turned it into a local farm, cultivating oranges and yucca. Just like every normal local farmer family, Natalia grew up between crops and animals, papayas and bananas, in an almost self-sustainable household. A couple years after buying the land, Natalia’s family started facing problems. At the end of the eighties, The Shining Path, a ‘communist turned terrorist’-group affiliated with drug trafficking, had a stronghold in their region.

Natalia explains: ‘They [the Shining Path members] presented themselves as ‘protectors of the town’ against other potential terrorist groups. The price they wanted was to not notify authorities of their presence.’ A situation this tense, eventually made a small conflict between Natalia’s father and another farmer turn into a matter of life and death. ‘Some of the farmland was about 2 hours away from town, so my father had a tractor that he rented out for other people’s convenience. Once, he had an argument with a renter about the fee and he decided to cancel the rent of the tractor. This led to a dispute and the other man apparently had reported him to the drug dealers, ordering for him to be killed. This led to my father being on a death list. The police found the list and notified him, took him to the station for protection, and gave my family the advice to leave the town. We left immediately and 8 years of our hard work was abandoned.’

Deforestation due to coca cultivation

An obvious impact of the widespread coca cultivation is the deforestation of several hundred thousands of hectares, often located in areas unfit for agriculture which would otherwise still be pristine nature. The deforested areas include land currently planted to coca, land used by the coca producers for subsistence farming, land that is abandoned after soil becomes infertile, land deforested by the coca producers who are dispersed as a result of political violence, and land on which landing strips, laboratories and camp-sites are built.

Deforestation for coca plantations can even be observed from space, as shown in the MAAProject by Amazon Conservation. The deforestation is approaching the limit of the Indigenous Huimeki Communal Reserve. Images show the deforestation of 390 acres (158 hectares) in this area in 2017.

In protected lands and those appropriate for forests, deforestation can be especially damaging because

- It creates the loss of soil through erosion

- Extinction of genetic resources

- Alteration of the hydrologic system

- Lack of wood, timber, food etc.

The almost mandatory burning of the debris left by deforestation brings with it other problems, such as

- Air pollution

- Topsoil deterioration

- The loss of soil nutrients

Cocaine paste polluting the forest

During the process of the preparation of basic cocaine paste, air, soil and water are contaminated. The impact on the environment of the preparation of basic cocaine paste is incomparably greater than that of agrochemicals.

While the air is polluted from all the smoke of burning forest, soil and water are contaminated during the process of alkaloid extraction from the leaves.

While the air is polluted from all the smoke of burning forest, soil and water are contaminated during the process of alkaloid extraction from the leaves. The extraction procedure involves two steps, the first is soaking the leaves and the second is cleansing and pressing to a paste. Although different recipes exist to extract cocaine from the coca leaf, the mixture usually involves sulphuric acid, kerosene, alcohol, benzene, quick lime, carbide, toilet paper and sodium carbonate to get to the raw or base cocaine. One specific recipe mentioned quantities: 18 liters of kerosene, 10 liters of sulphuric acid, 5 kilograms of quick lime, I kilogram of carbide, and 5 kilograms of toilet paper for every 120 kilograms of coca leaf. For the cleansing and pressing, processors use 11 liters of acetone and 11 liters of toluene for each kilogram of basic paste produced.

Kerosene, although moderately toxic, severely affects the biology of water flora and fauna, especially of plankton. Sulphuric acid is extremely dangerous, as are all the other substances that are dumped, such as carbide, calcium carbonate, acetone and ammonia. Not even the toilet paper is harmless. Many unsuspected compounds and recombinations of these substances are concentrated in certain aquatic organisms, and undoubtedly reach humans through the food chain.

A survival of the fittest

According to the latest Global Witness report, Peru is among the ten most dangerous countries for Earth defenders. Since 2011, more than 45 environmental rights defenders have been killed. Often, these threats and murders happen to people defending their community and land against drug traffickers.

Peru is among the ten most dangerous countries for Earth defenders. Since 2011, more than 45 environmental rights defenders have been killed. Often, these threats and murders happen to people defending their community and land against drug traffickers.

During the recent political protests in Peru, it was initially believed that the uproar was caused by drug lords. Unrest erupted after president Pedro Castillo was impeached and his vice president, Dina Boluarte, took power. Most of the protests took place in the south of Peru, close to the Bolivian border and in the VRAEM region. So far, at least 60 people have been killed in the upheaval.

The new president was fast in accusing the demonstrators of liaising with drug traffickers. Stating that ‘the most violent demonstrators are organized by narco-trafficking groups, the illegal mining industry and political activists in nearby Bolivia.’. However, Peru’s foreign affairs minister since then contradicted its president about the origin of deadly protests shaking the country, saying in an interview last month ‘we don’t have any evidence’ that the demonstrations were being driven by criminal groups.

Some local leaders of the protests were associated with the Shining Path, but its only surviving military faction ‘the Militarized Communist Party of Peru’, operates in the rainforest as a protector of narco trafficking organizations and apparently took no presence in the demonstrations. Such accusations are perceived as deeply offensive to the protesters from rural areas, as many of them had confronted and defeated the Shining Path in the countryside in the late 1980s.

Shining Path

Much of Peru’s coca is produced in the VRAEM region and what remains of the Shining Path has teamed up with local drug trafficking gangs in that region to control the trade.

The Communist Party of Peru – Shining Path, was formed in 1970 as a breakaway faction from the Peruvian Communist Party (PCP). Though the Shining Path remained small, with around 3,000 members at the peak of its power in 1990, it was responsible for the majority of the victims of the war that followed — the Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that it killed some 31,000 people between 1980 and 2000. The group’s methods were particularly brutal, including stoning victims to death, or placing them in boiling water. The Shining Path carried out massacres of peasant communities perceived as being against their struggle, as well as attacking the security forces and other representatives of the state. They quickly gained ground, and were present across vast swathes of Peru by the end of the 1980s.

The massacre of 16 people in May 2021 near the village of San Miguel del Ene marks a major return to violent actions by the Shining Path. Currently, the remnant group of the Shining Path finds itself in a narrow but strategic drug trafficking corridor between the departments of Junín, Ayacucho and Huancavelica in the VRAEM, the country’s main drug producing region. The heart of the jungle of the VRAEM, is a strategic location for controlling key drug trafficking routes towards Brazil and Bolivia.

The police didn’t have any power, they could only warn people for the acts of the Shining Path and the drug traffickers. It was ‘nobody’s land’, and we had to protect ourselves.

Natalia Campana

Natalia remembers the time living with the presence of the Shining Path as deeply scarring: ‘The police didn’t have any power, they could only warn people for the acts of the Shining Path and the drug traffickers. It was ‘nobody’s land’, and we had to protect ourselves.’ ‘Living in the jungle was beautiful but I still remember the emotions of my parents – a continuous feeling of anxiety. After the threats, we left at once and the sudden change, the sudden abandonment of the farm, the search for a new future, traumatized me.’ Natalia was 5 years old when they moved to Lima and she did not speak for a full year.

Some of Natalia’s family still live in the VRAEM region: “These days, the terrorist groups are less, but the people in the countryside still have to obey the rules of the drug dealers. We say ‘no vayas al fondo’: don’t trespass or cross any borders. Don’t mess with them, and they won’t mess with you.”

Natalia continues, upset: “Sometimes, in Peru, we normalize these problems. As if ‘people from the jungle are used to it’. But it’s not normal. This is not the way we should live.” Natalia says that what happened to her family, a dead threat that made them abandon their land, could happen to anyone. “The drug traffickers start conflicts between farmers, the drug dealer interferes and tries to ‘solve’ the problem, small problems get bigger, and then people are forced to leave their land. People don’t realize how much effect it has to live in such danger and stress.”

People work on the land for 20 soles a day, risking their lives, for our economy and food. We need to protect their integrity and safety. How are we going to eat that food if those people are under threat of being killed?

Natalia Campana

Natalia stresses how this situation causes long-term emotional problems. “We should feel more empathy and have attention for the story of others, even if it’s not your story or country. People work on the land for 20 soles a day, risking their lives, for our economy and food. We need to protect their integrity and safety. How are we going to eat that food if those people are under threat of being killed?”

What could solve the issue?

Eradication

In an attempt to eradicate the illicit cultivation of coca, governments in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia started destroying fields of coca already back in 1961. In Colombia, spraying herbicides was a used eradication technique, but since 2016, only manual eradication has taken place. Aerial spraying of glyphosate herbicide, one of the most controversial methods of coca eradication, has taken place in Colombia exclusively because of that government’s willingness to cooperate with the United States in the militarized eradication of coca after signing Plan Colombia in 2000.

In Peru, about 25 thousand hectares of coca crop are manually destroyed on a yearly basis. In a joint fight – ‘the war on drugs’ – the United States is supporting the Peruvian Government’s eradication efforts, including eradication in Puno and in the VRAEM region.

Unfortunately, manual eradication – burning and cutting of the crop – also harms the environment as it causes soil erosion and once a plot is destroyed the planters simply move further into the forest, clearing new lands for coca production. It creates a vicious cycle of unsustainable cultivation-eradication.

Governmental control

Governmental control of coca cultivation seemed another promising solution. In Peru, the General Law on Drugs enacted in 1978 prohibits the cultivation of coca and seedlings in new areas within the national territory. In the same year, another law established the National Coca Enterprise (ENACO), which has a monopoly on the commercialization and industrialization of coca leaves. Therefore, the selling of coca leaves to any party other than ENACO is considered illegal by national law.

It is estimated that there are some 62,000 hectares of leaf crops in the country and national production would be around 160,000 tons. The company pays 100 soles (26 dollars) for the arroba (of 11.24 kilos), according to local media. However, in recent years ENACO has purchased only 2,500 tons a year from the 95 thousand registered legal coca leaf producers. A new plan is now in the making (at least, this was the impeached presidents’ plan) to purchase all coca bush nation-wide, including from approximately 400,000 unregistered producers.

But coca cultivation and transport doesn’t have to be as violent as it currently is. Between 2006 and 2019, Bolivia emerged as a world leader in formulating a participatory, non-violent model to gradually limit coca production in a safe and sustainable manner while simultaneously offering farmers realistic economic alternatives to coca. In certain parts of Bolivia, the drug trade is part of a local moral order that prioritizes kinship, reciprocal relations and community well-being, facilitated by the cultural significance of the coca leaf. The Peruvian government has made a tentative move towards implementing one aspect of Bolivia’s community control in Peru. Studies show that successful participatory development in drug crop regions is dependent on land titling and robust state investment, which strengthens farmers’ involvement and avoids recurrences from the past.

Alternative Development

Another more radical and long-term solution is offered by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. They support the introduction of alternative development in areas like forest management, the protection of ecosystems in indigenous communities, livestock raising and the development and consolidation of legal and self-sustained economies through the marketing of palm oil, heart of palm, cacao and coffee.

Just Say No

Despite the devastating and deadly consequences of cocaine addiction, it is just as often used as a punchline or featured as the luxury drug of choice among the super rich in movies and pop culture in the United States. We are more likely to think of Al Pacino in an expensive suit contemplating his mountain of cocaine in Scarface, Leonardo DiCaprio snorting a line of cocaine with a $100 bill in Wolf of Wall Street, or a drugged, crazed bear tearing through the woods in the recently released Cocaine Bear, than we are to think of the families in the cross-fire a world away–– families like Natalia’s.

The consumer can stop this entire industry immediately by the act of saying NO. Peru isn’t a mass consumer of cocaine, it’s the Western world who fuels this business.

Natalia Campana

Natalia has the perfect and most simple solution to end the use, trade, trafficking and cultivation of coca and cocaine: ‘The consumer can stop this entire industry immediately by the act of saying NO. People in the rest of the world are indifferent to the story behind cocaine, as they are disconnected from what is happening in our country. Peru isn’t a mass consumer of cocaine, it’s the Western world who fuels this business.’